Last week I wrote about gender-inclusive language in early Christian literature - specifically the period between the apostles and Augustine (roughly 100-451 CE). I noted that because of the inherently male dominated world of theology and thought at that point in time, much of the language used to describe the Godhead had masculine pronouns (God as he) and all relationships were describe in male terms (Father, Son).

However, much of the theology they describe cannot be extracted from underneath the baggage of masculine language simply because it is so essential to what they're trying to describe. For many of these early thinkers, God is the Father precisely because Jesus is the Son; God is Almighty because of the existence of creation - I'm looking at you, Gregory of Nazianzus. The description of the relationship between God and Jesus is inexplicably mixed with the Father/Son language; it is an essential point of their argument that we consider God and Jesus within the structure of a parent-child relationship.

Consider the example of the king in Antoine de Saint-Exupery's The Little Prince. As the little prince travels from his little planet, he comes across several people, one who is a king. However, he's the only person on the planet, begging the question of what he really is king over. Although the king would argue he's king of his planet and the stars and universe, there is nothing there that makes him a king. Having a kingdom is an essential part of being a king. This example applies to some of the arguments made by early Christian thinkers; God is God because of the relationships God has with creation and Jesus. God is God the Father because Jesus is a son.

Much of their writings were the foundation for theology from then on; their writings were referenced and built upon for centuries by theologians who created systematized theological doctrines. Both the original writings and the later writings based on church fathers are still influential today. These texts are not just a part of the distant past; they continue to impact and shape current theology. The inherent gendered relationship became institutionalized; while some people throughout the ages have found ways to incorporate alternative metaphors (the medieval mystics are particularly good at this), it's largely been dominated by the father-son relationship.

A large project for future study would be a re-thinking of these early Christian theologians, an attempt to try and describe the relationship between Jesus and God without automatically falling back on father-son language; to extract their meaning and place it in an inclusive setting. Some of the terms used for Jesus in the Bible include (in addition to Father/Son language) logos (Word) and Sophia (wisdom). It's possible to be more inclusive and it's biblically based as well.

Bringing in these inclusive terms doesn't invalidate the father-son relationship as described by the early thinkers; it adds to it. The problem occurs when we rely exclusively on one metaphor without fail. If God is incomprehensible, then we should be using as many ways as possible to describe what we experience. For every God the Father, we should use a God the Mother. For every God as Lord, we should incorporate God the servant.

While this focused mainly on the role of gendered language in early Christian theology and literature, another topic worthy of discussion is gendered language today. A comment on the earlier post actually inspired this post, but looking back, I realize that I only further clarified the points already made without addressing the Jesus as Son language used in today's theology and liturgy. I will address that in a future post, however, if someone is interested in this topic, I suggest Elizabeth Johnson's She Who Is and Rosemary Radford Ruether's Sexism and God-Talk. I really enjoy Johnson's book and will be reading it in the scant free time I have before my next semester starts.

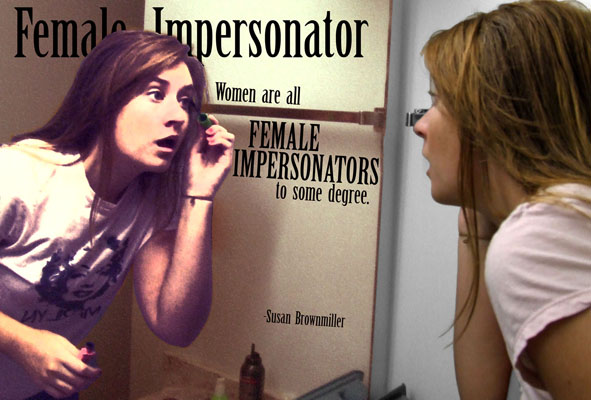

To get you started thinking about this language, I leave you with the concepts of imago Dei and imago Christi - the image of God and the image of Christ. What does it mean for one to be imago Dei? What does it mean for a white, hetero man to be imago Dei compared to a queer woman of color? Or anyone, for that matter? What does imago Dei and imago Christi look like?

Saturday, December 20, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

6 comments:

Great post, Lindsay. I think you did a great job addressing this issue in both your posts. I hope people who were dissatisfied with your last one come back to read this.

I rejected one of Mike's comments because of his repeated use of loaded terms that I did not feel comfortable with.

If he reads this again, I suggest to him to re-state his argument without resorting to commenting on the poster.

Just a head's up.

Hey Lindsay, I keep commenting because I find myself having to moderate inappropriate comments on your well-written posts.

Mike seems to be coming out as a bit of a troll (using words like "feminazi's", "pathetic", and "pitiful." I wonder if he's someone who has commented here under a different name...

Thanks for all the hard work you do anyway!

For every God as Lord, we should incorporate God the servant.

I think in my understanding, the "servanthood" aspect of the Godhead is encompassed by Christ, while the "Lordhood" aspect is encompassed by YHWH.

In terms of your question re: "imago dei" and "imago christi", I have been fond of talking about "The 6 billion faces of God" both to express this idea, and also to suggest that God's interactions with His/Her/It's/Their (a pronoun for a deity that is many-in-one and one-in-many, and all genders, is hard to pick!) people, has to be essentially individual - God will have a different "appearance" depending on to whom God is communicating. The Prophets in the OT strike me as a classic example: Ezekiel, a very ritual-based man, receives visions and messages couched in very ritualistic styles; Jeremiah's messages are in tune with Jeremiah's own personality, and so on.

This, of course, feeds back to your point about needing to use more than one metaphor, more than one angle of view, to appreciate the wonder of the Godhead, of the Lord and of the Christ.

Since God is infinite, and we are but a finite part of His(etc) Creation, for us to comprehend the totality of God's splendour is impossible, just as it's impossible to know the exact and true value of π.

I hope you continue to monitor this post, but I think it's important.

I come at it from a straight (sorry: no pun intended) orthodox position, and I fight with people all the time about this issue -- some of them my closest friends. And I think the issue roots in a fundamental disagreement about what is at stake: For me, "Father," "Son," and "Holy Spirit" are not metaphors that can be tossed out, but they are the revealed Names of God the "Trinity." They, of course, have metaphoric overtones and meaning -- especially in the extent to which they posit a relational character to the Godhead (what a hiddeous term) rather than a kind of Greek philosophical staticism.

The human problem (perhaps "The" original sin) is that we try make ourselves the dominatrices of the universe: We want things to comport with our view of reality. Thus, if "father" is a male figure in our heads, then "Father" is an inadequate "image" for God. Yet, Jesus himself called on us to call the One who sent him and to Whom he had recourse in his hope "Father" -- not "like-father".

Part of the metanoia of Christian faith (we can't require it of any other faith tradition, of course) is the "Breaking" of our images, thought-patterns, "paradigms," and the like on the reality of Christ -- following him, not as a springboard for our speculation, but as the molder of hearts, souls, minds, and strengths.

On the de-genderizing of language, then, I raise one question: Which member of the Trinity is not "creator" (as I read Genesis 1, they all are) or "redeemer" (what did Jesus do that God was not involved in, e.g.) or "sustainer." The danger of Modalism is that it posits a different God from the one we claim in the Name of Jesus through the power of the Holy Spirit.

Keep thinking, people, but don't let your thoughts be untied from the Great Tradition.

DwightP

Post a Comment